Have you ever thought about why it’s so hard to remember the name of someone you met recently at a party or meeting, yet so easy to recall special moments like your graduation day or your first day at college or work? However, if the name is associated with an important event or is very similar to someone you know, it becomes easier to remember. The reason we can recall long-term memory but often forget short-term (or immediate) memory lies in how the brain processes, stores, and retrieves information.

What is memory?

Memory is an important part of human cognition, it helps us in retaining the past, navigating through the present, and planning for the future. It is the substrate upon which personal identity is built. The modern scientific framework understands memory not as one thing, but as a collection of multiple, distinct, and neuroanatomically dissociable systems.

Long-term memory systems

Long-term memory systems refer to the part of our memory that is responsible for storing information over extended periods ranging from hours to an entire lifetime. They are broadly classified into Declarative (Explicit) and Non-declarative (Implicit) memory.

1. Declarative memory – It encompasses all the information that we can consciously and intentionally retrieve and declare. This system stores our knowledge of facts, ideas, events, and personal experiences, forming the narrative of our lives and our understanding of the world. The knowledge stored by declarative memory can be accessed and applied in various contexts, different from the one in which it was learned.

2. It is further subdivided into Episodic and Semantic memory

a. Episodic memory: Episodic memory stores information about events we have personally experienced. It is the ability to re-experience a past event and remembering specific details about what, where and when. Examples of episodic memory are remembering graduating high school or recalling performing an adventure activity or sport.

b. Semantic memory: It is composed of facts, concepts, and knowledge that are independent of the learning context. This system holds our vocabulary, our understanding of objects, and our factual knowledge base. For example, knowing the capital cities of a state, remembering important historical dates or knowing the use of legal documents.

1. Non Declarative memory – Non-declarative memory operates outside of conscious awareness. It refers to information that is acquired and used unconsciously, influencing our thoughts and behaviours without our intentional effort or even our awareness that we are drawing on a memory.

It is further classified into procedural, priming, and associative learning

a. Procedural memory- Procedural memory is responsible for the acquisition of our skills and habits. We perform complex tasks automatically such as riding a bicycle, swimming or typing without much conscious thought. After sufficient practice, these skills become ingrained and can be executed with less effort. It is also known as “muscle memory.”

b. Priming- Priming is a form of implicit memory that typically happens outside conscious control. It is a phenomenon where exposure to one stimulus influences one’s perception and behaviour, thereby influencing the response to a subsequent stimulus. For example, while driving, if you see a public safety hoarding showing an image of a car crashe caused by speeding, you find yourself driving more cautiously.

c. Associative learning- It is a form of implicit memory which is critical for survival. The brain learns to connect events or stimuli. It is a powerful mechanism that underlies many of our emotional and physiological responses. A classical example is Pavlov’s experiment where the dog salivates at the sight of food before learning has taken place. During the learning phase, when a stimulus of a bell ringing is introduced before giving food, the dog develops a conditioned response over time. After learning, the dog salivates when the bell has been rung, even though food is not given.

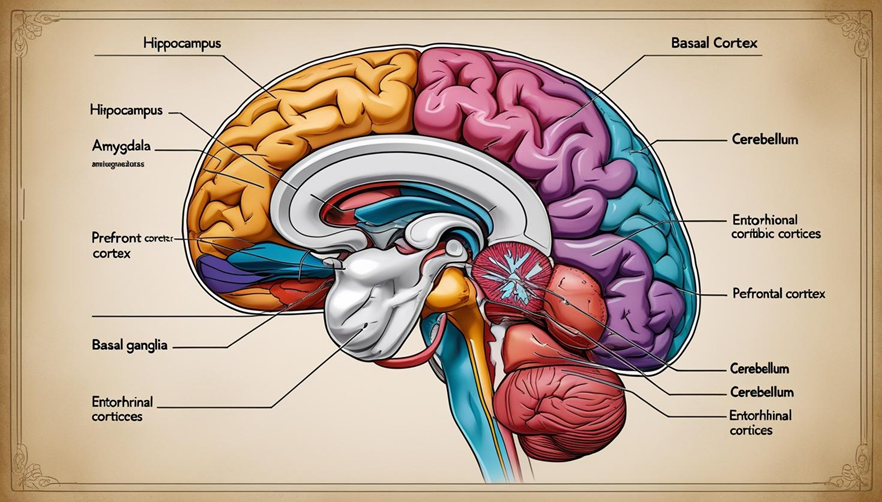

The Neuroanatomy of Memory: A Distributed Cerebral Network

The hippocampus, amygdala, neocortex and surrounding cortices in the medial temporal region of the brain are responsible for Declarative memory, while the basal ganglia and the cerebellum manage Non- Declarative or Implicit memory. It is the primary substrate for working memory, the ability to hold and manipulate information online for brief periods to guide behaviour.

- The hippocampus encodes new experiences

- The amygdala tags emotional significance

- The prefrontal cortex organizes and retrieves when needed

- The basal ganglia and cerebellum store routines and motor memory

- The entorhinal cortex and thalamic structures help integrate and relay memory signals.

When Memory Fails: Pathologies and Therapeutic Horizons

Alzheimer’s Disease:

It is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by an insidious onset causing a decline in memory and other cognitive functions, including language, reasoning, and judgment. The pathology initially affects the medial temporal lobe and spreads outward into the neocortex. It moves through the temporal lobes, affecting language and semantic memory, and then into the parietal lobes, impairing visuospatial skills and navigation, eventually reaching the frontal lobes. This progression leads to widespread brain atrophy, with significant loss of neurons and synaptic connections, and a visible shrinkage of brain volume. At the microscopic level, the brains of individuals with AD are defined by the accumulation of Amyloid-β (Aβ) Plaques and neurofibrillary tangles which are major contributors to neuronal dysfunction and death.

Basal ganglia and cerebellum circuits are affected much later, thus implicit memory is retained even in the advanced stages. This explains why a person may be able to play a familiar tune on the piano (preserved procedural memory) but may not recognize their family member (declarative memory failure)

Alzheimer’s disease treatment includes anti-amyloid treatments, such as monoclonal antibodies for their ability to slow cognitive decline. Other strategies in development include anti-tau therapies, novel neurotransmitter regulators, and compounds aimed at reducing neuroinflammation.

Compensatory aids for memory impairment

- Journals

- Sticky notes

- Calendars

- Calendar reminders

- Alarms

- GPS navigation

- Digital clock

- Bluetooth trackers

Memory reconsolidation to treat maladaptive memories

Memory reconsolidation is widely used for treating PTSD, phobias, and addiction by reconditioning harmful emotional memories. The therapeutic strategy involves three key steps: (1) reactivating the specific maladaptive memory through targeted recall, (2) administering an intervention during the subsequent window of lability to disrupt its reconsolidation, and (3) allowing a new, weaker, or updated memory to be re-stabilized.

Conclusion

Memory is not just a storage device, but a dynamic, multifaceted process. With discoveries such as optogenetics, it is now possible to identify and update the engrams of a memory trace. Consolidation and reconsolidation show that memory is a reconstructive process. Our recollections are not static recordings but are actively stabilized, reorganized, and updated throughout our lives, a feature that provides both the capacity for growth and the potential for therapeutic intervention. As we continue to decode the mechanisms by which we store our past, we move closer to being able to protect, repair, and perhaps even enhance this most fundamental of human capacities.

Leave a Reply